The decline of mechanical stock screening

Living day to day, we can’t really appreciate the pace of technological change. So, before we get into stock screening, let's summarize the last 83 years of electronic financial data systems in 5 sentences.

In 1960, Scantlin Electronics introduced Quotron I, the first magnetic tape storage of stock prices. Before this, people used printed ticker tape.

In 1982, a man, fired from the Salomon Brothers, created the Market Master Terminal, which became known later as the Bloomberg Terminal. People could see not only prices but also financial statements.

In the 2000s, a bunch of data providers (Capital IQ, Refinitiv, etc.) came into the game, providing such advanced data as segment analysis.

It’s appropriate to think that technological innovations are good, but the funny part is that investing was easier 60 years ago than it is now because it was local. Investors needed to call the company to get the last financial report by mail (physical, yes) or use printed services like The S&P 500 Guide or Value Line that aggregated the company's information. A few people had brokerage accounts, but even fewer of them wanted to dig through hundreds of financial statements by hand.

And here we are right now, when a guy from Australia, Japan, or any other country can open a website and get the data about every trading company in the world sorted by almost any financial parameter, and do this in 30 seconds for a small amount of money (sometimes even for free).

Multiply it by the number of retail investors with value-growth-dividend-momentum investing books in their hands, and you’ll get an approximate view of how much pressure markets get and how fast every inefficiency in price is eliminated.

Does it mean investors can’t beat the market? No, it just becomes harder to find a company with good fundamentals and an adequate price using a screener, no matter how fascinating the filters are.

The way to go? We need to look for accounting inefficiencies. To put it simply, financial data that can’t be found or parsed through screeners.

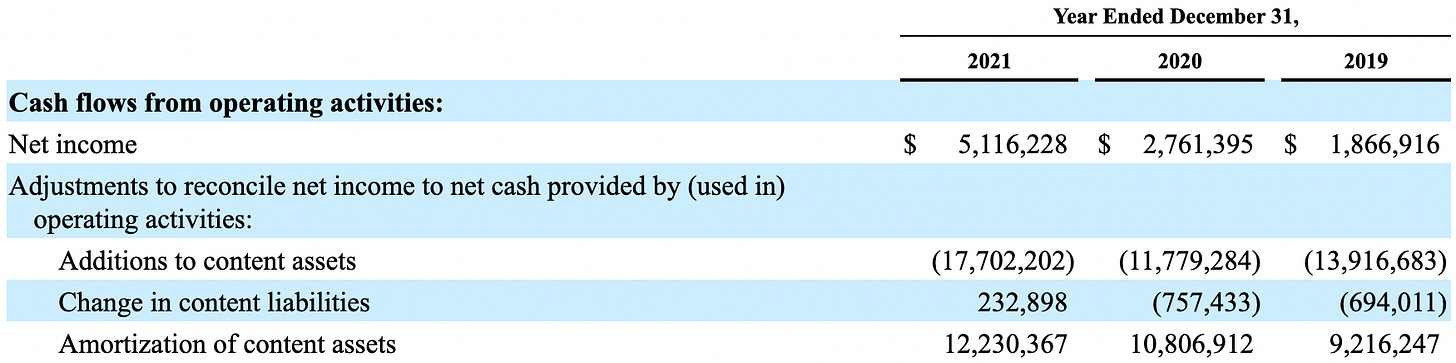

Take Netflix, for example. It has $30.9 billion of content assets, but if we look closer, we’ll see that $13.8 billion is licensed (rented) assets from other production studios, and only $6.9 billion is owned by the company itself. Furthermore, the company says, "On average, over 90% of a licensed or produced content asset is expected to be amortized within four years after its month of first availability." So the nature of this licensed asset is more like a prepaid rent that’s going to expire in 4 years and the residual value is 0. I don’t need to say here how it can affect the value of the company and the price investors should pay.

No screener can show these opportunities, and by exploring them, people can thrive as investors. Yes, they have to put in more effort than just 20 years ago, and it’s going to be harder in the future.

You might think now that the only way to find these inefficiencies is to look through every company. And you’ll be right. A lot and nothing changed during the course of 60 years of innovation.

We still have to dig through every company by hand, but now we don’t need to order financial statements by physical mail; instead, we can open a browser and download everything we want.

The final point we need to discuss is time. The sooner an investor starts digging through every company, the faster he finishes. Taking into account approximately 4,000 U.S. listed companies and the availability to check two companies a day, one can expect to accomplish the task in 5.5 years.

Sounds crazy, yeah? But there are two simple tricks that can be applied to the selection process.

The first trick is to choose just two of the 20 sectors in the stock universe. Specializing allows an analyst to avoid completing broad research twice, helping him to improve the quality of choosing other stocks in the same industry while saving time. The next logical step is to pick an industry, of course.

The second trick is to choose the hard-to-deceive filters in screeners. In other words, investors need to use the most stable filters across companies.

For example, filtering stocks by earnings per share can be misleading and eliminate good companies. In this case, the number of profitable years for the last 10 years might be a better solution to sort dead companies from promising ones. Because of the usual underperformance of new companies in the first years of their debut [2], and the financial "dress-up" for market appreciation, IPO dates can also help investors a lot.

In summary, there are no easy trades anymore, as well as a magic formula for selecting stocks, and investors need to look deeper into the financials. Every time someone is tempted to select easy-to-find, accurate criteria for high-yielding stocks, he should consider how many other investors are looking at the same stocks at the same time. There is no extra profit when there is competition.

Yes, it can sound tedious to sit all day and read hundreds of financial statements and industry reports, but this is exactly where the high return was 60 years ago and is today.

Vlad Chernikov

founder of roic.ai

All data and information is provided “as is” for informational purposes only, and is not intended for trading purposes or financial, investment, tax, legal, accounting or other advice. Roic.ai does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, completeness or availability of any information and is not responsible for any errors or omissions, regardless of the cause or for the results obtained from the use of such information.

[1] https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/reports-of-corporates-demise-have-been-greatly-exaggerated

[2]https://www.cnbc.com/2021/12/07/tech-ipos-a-bad-bet-in-2021-all-but-one-in-bear-market-territory.html

Agreed about the limits of screeners. I don't do it precisely the same way as you do Vlad, but I can very much see your way working.

Love ROIC.ai by the way, thanks for running the site. I think I'll post about it on my substack this week.